The EVC continued its remorseless policy of consolidation. Before the end of the year the Riker Electric Motor Vehicle Company, of New Jersey, had been bought out.

Andrew Lawrence Riker had lashed together his first electric car by cannibalizing two Remington bicycle frames in 1894 with a metal cradle and a motor. Two years later, in 1896, he finished second to an electric vehicle entered by Morris and Salom in a heat for a closed-circuit dirt-track race held at Narrangansett Park in Rhode Island. Despite bad weather, a crowd of 5,000 spectators gathered to watch the event. Riker’s entrant made the fastest mile time of 2min 13sec, but the Morris and Salom vehicle had greater endurance. Scientific American magazine reported that Riker received the first prize of $900 and the runner-up prize of $450 went to Morris and Salom.

Riker was bitten by the racing bug. His electric vehicle performed with distinction in Boston (where it won the braking contest) and the first race meeting of the New York Automobile Racing Association held at Aquidneck Park on 6 September 1900.

However, Riker was not blind to the drawbacks of electric vehicles. The Electrical World magazine of 23 January 1897, reported an address Riker made to the American Institute of Electrical Engineers in which he sounded a note of caution that contemporary battery technology was not sufficient for the electrically powered vehicle. Summing up, he told distinguished guests that such vehicles ‘did not appear to be suitable for long-distance travelling, but would be principally successful as pleasure vehicles, where the short-lasting qualities would not be objectionable and where their many superior advantages would place them in a very superior position’. Riker set up a company to manufacture electric motors based on ideas he had patented, then quickly moved on to full-scale vehicle production. He used bicycle frames for light weight and strength.

Anxious to prove his inventions in competition, on 16 November 1901, his torpedo racer (named after its torpe-do-like nose) set a new world speed record for electric cars in a speed trial held at Coney Island, New York. Riker managed to drag his car down the 1-mile dirt track straight in just 63sec. His record was unbroken for 10 years.

His company also manufactured a number of straightforward runabouts that could seat two people and were driven by two electric motors connected to the rear axle by spur gearing. Their maximum speed was 10mph (16km/h) and the battery pack was good for a range of 25 miles (40km). The wheels were shod with pneumatic tyres and the controller gave three forward speeds and two reverse. The upmarket phaeton deluxe model had been shown at the 1898 Paris automobile show. Riker also built four-seater carriages that were propelled by a pair of 3bhp motors of his own design, which gave a 12mph (19km/h) top speed.

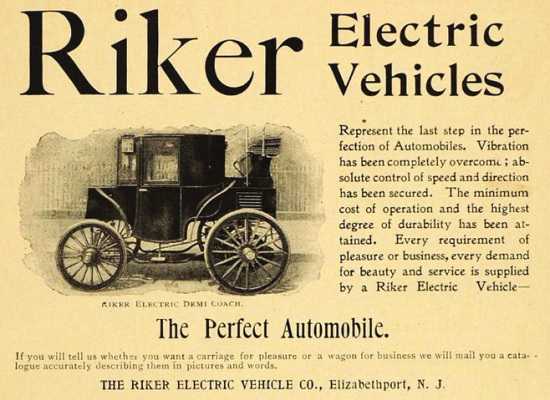

By 1898, Riker had a full range – a two- and four-passenger trap, the posh phaeton, a victoria, a surrey, a wagon and a tricycle. With typical American modesty the vehicles were advertised as ‘the last step in the perfection of automobiles’.

The ads went on: Vibration has been completely overcome; absolute control of speed and direction has been secured, every requirement of pleasure or business, every demand for beauty and service is supplied by the Riker electric vehicle.

Not everyone was able to testify to the Riker’s ‘absolute control’ as one amusing story in the London-based Motor Car Journal of 21 July 1899, attested. The writer, having borrowed a Riker from a Mr Frost-Smith, was travelling downhill by Highgate Station and overtaking another vehicle when a cyclist suddenly appeared in front of him. The innocent biker panicked at the sight of two horseless carriages charging toward him and tried to pass between them but, as the article put it, ‘an accident was inevitable’.

The report continues:

Our brake was jammed hard, the vehicle swerved, caught the kerb, travelled on two wheels for a yard or two, and then the driver and writer were both sent flying…. Quickly picking ourselves up and finding no bones broken, we gazed around, saw the car had been turned on its side, one wheel buckled, spokes bent and broken in another; the acid was pouring out in gallons and the wheels were revolving at great speed.

The poor cyclist was pulled to his feet having suffered a severe scalp wound and lost the sole off one of his shoes. Luckily for all concerned the article concludes:

The accident happened opposite the Winchester Arms [a pub], and the landlord did all that a man could do to assist, and performed nobly the work of a ‘Good Samaritan’.

Presumably with free pints of beer all round. It seems most likely that Whitney and the Electric Vehicle Company were interested in Riker’s commercial vehicles.

According to a feature in The Horseless Age (October 1898), the truck consisted of a tubular steel frame and a motor mounted on the rear axle, which rode on elliptic springs. The batteries were modular – fitted in crates that could be varied according to distance and load. Recharging was simple and the batteries cut themselves off when full. An automatic circuit-breaker beneath the seat disconnected the batteries in the event of an overload on the motor. Riker claimed a range of 25–30 miles (40–48km) and a top speed of 15mph (24km/h).

The following year, the firm introduced a real workhorse: a delivery wagon which rode on wooden wheels and 3-inch solid rubber tyres (presumably because its weight would have burst conventional pneumatic tyres). The weight of the vehicle, which had a 68-inch wheelbase, was 3,600lb (1,633kg) and its carrying capacity 1,000lb (453kg), in addition to the driver and delivery man. Top speed from the twin motor set up was a modest 9mph (14km/h) and the range was said to be 30 miles (48km). Riker also marketed a mail wagon for postal deliveries, some of which were used in Washington DC for a time, and a delivery wagon, which was used to transport carbonated water in New York.

Such a tempting array of commercial vehicles made the company a natural fit for the EVC and at a meeting of the board of directors on 6 December 1900, Riker agreed to sell the company.

Reporting the deal, The New York Times said:

The absorption of the Riker Company will give the Electric Vehicle Company, according to the statements of its officers, a complete monopoly of all the patents for manufacturing electric vehicles in this country, and will probably also give it control of all the patents for gasoline vehicles.

No money changed hands. The takeover was a simple exchange of stock. As part of the deal, George H. Day, the former president of the Columbia Electric Vehicle Company, became president of the newly enlarged EVC.