In 1979, the Middle East was thrown into chaos when Islamic revolution swept the Shah of Iran from power and replaced him with the Ayatollah Khomeini. Foreign oil-workers fled for their lives and Iran was forced to suspend oil exports, prompting a second oil crisis in less than ten years. Although Saudi Arabia and other OPEC members increased output to off-set the loss of production, the price of a barrel of oil more than doubled.

Panic-buying exacerbated the problems. In the United States, the world’s biggest car market, it was estimated that drivers were actually wasting 150,000 barrels of oil a day simply sitting in gas station queues waiting to fill up.

The second oil crisis caught American car-makers by surprise. Despite the Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) regulations, which had come into force in 1978, Detroit’s Big Three auto-makers were still peddling overstuffed gas-guzzlers. Cars like the Ford LTD were physically smaller than their predecessors but they still relied on large-capacity V8 petrol engines. As another fuel crisis gripped the world, Japanese manufacturers cashed-in with cars that used smaller fuel-efficient multi-valve engines and front-wheel drive. Soaring pump prices also acted as a pretty big incentive for car makers to pursue alternatives to fossil fuels with renewed vigour.

One of the first concept cars out of the blocks was from an unusual source. Briggs & Stratton, best known for its lawn-mower engines, unveiled its vision of the future, a bizarre-looking six-wheeled gasoline/electric hybrid car, in 1980. The company had dabbled in automobile design (of a sort) 66 years earlier when, in 1914, it bought the rights to the Wall Auto Wheel, a strange go-kart lookalike that had been developed by Arthur Wall, in Birmingham, England.

The company sold the patent to the Automotive Electric Service Company in 1923 when it became an EV – the small internal combustion engine was replaced by a motor and 12V batteries.

In 1980, Briggs & Stratton management decided to create a petrol–electric hybrid. However, as development funds were strictly limited, it did so using off-the-shelf parts. As a result, the twin-cylinder 694 cc engine was ‘borrowed’ from a garden tractor and combined with an 8 bhp motor removed from a treadmill drive.

The batteries were originally intended for an electric motor boat. Unfortunately, the combined power of this parallel hybrid design was a mere 26 bhp – a severe limitation in a car that carried a 1,000 lb (454 kg) lead-acid battery pack and required twin rear axles.

The car’s fibreglass body was designed and styled by Brooks Stevens, who was better known for his work on Harley Davidson motorcycles, and another Milwaukee-based company, Johnson Controls, helped out with the powertrain controller. One innovative feature was a flip switch that enabled the car to run on batteries, gasoline or both.

Although the hybrid concept featured a racing bucket-seat, its performance was modest, to say the least. On a long enough stretch of road it could just about struggle to 70 mph (112 km/h) but a more realistic top speed was 50 mph (80 km/h). On battery power alone it could travel around 30 miles (48km) and recharged from a standard power outlet.

The company boasted that it had ‘advanced the electric car a step closer to a practical reality’ and described the six-wheeler as a ‘sporty family sedan’. ‘On short urban commutes, the electric power is ideal – economic and clean at speeds up to 40 mph (64 km/h),’ it went on. ‘For longer trips, where extra power is needed, the hybrid uses both motors to overpower hills or maintain cruising speeds up to 55 mph (88.5 km/h) for nearly 300 miles (483 km) between gas pumps. If electric power runs low, the gas engine alone can get the driver back home, where he can plug into the battery charger.’

Once it was finished, Briggs & Stratton maximized the company’s investment by sending the hybrid out on the road. It was taken to Washington DC for an Earth Day event, driven in rush-hour traffic and sent to San Francisco, where it climbed the city’s steepest hills (albeit rather slowly). American Indy Car and Formula One legend Mario Andretti even drove it on a parade lap at the Road America track in Elkhart Lake, and another race driver, Johnny Rutherford, used it to set a bunch of national speed records for hybrid vehicles. The project cost around $300,000 and the company certainly got its money’s worth in terms of publicity, but its long-term hopes for the concept came to nothing.

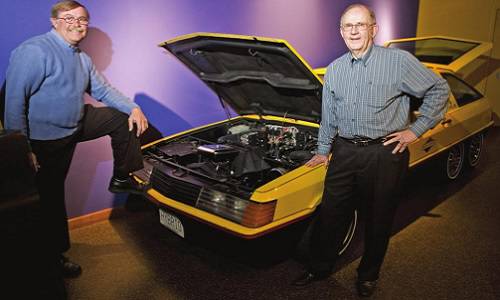

According to Bob Mitchell, who was the company’s manager of advanced research, Briggs & Stratton never had any intention to put the car into serious production. He told the Milwaukee-Wisconsin Journal Sentinel that it hoped instead to supply engines and motors to other companies already working on electric vehicles and hybrids.

‘The idea was that cars really didn’t need hundreds of horsepower to go down the road,’ he explained. ‘If you were willing to drive at a moderate speed, saying 40mph without a lot of acceleration, then perhaps 12 horsepower would be enough.’ The six-wheeler now lives out its retirement at the Briggs & Stratton museum in Milwaukee.