As the fifties drew to a close another company was preparing to launch an electric car on to the American market. Bankrolled by an ambitious would-be motor magnet, the Henney Kilowatt had a powertrain built by a vacuum cleaner company that was installed in the body of a Renault Dauphine. Quite why the Henney Motor Company, a respected limousine coach-builder best known for its funeral cars and work for the Packard Automobile Company, selected the quirky Renault as its donor chassis, when there were plenty of domestic alternatives, is unclear.

The Kilowatt was the idea of millionaire C. Russell Feldmann, who bought the Henney Motor Company in 1946 and harboured ambitions to become a major motor manufacturer. Indeed, Feldmann had a long association with the car industry having made his first fortune with the Automobile Radio Corporation, which he set up in 1927 to sell the Transitone, one of the very first in-car radios.

By 1946, Feldmann was a very wealthy individual thanks to his controlling interest in the Detrola Corporation, one of the largest manufacturers of domestic radios in the world. Henney, based in Freeport, Illinois, would become the object of Feldmann’s new obsession: the creation of a new generation of electric vehicles.

In 1953, Henney bought Eureka Williams, one of the country’s leading manufacturers of vacuum cleaners and a range of domestic waste-disposal units rejoicing in the wonderful name of the Dispos-O-Matic. Eureka had been waging a largely unsuccessful war with Hoover in a bid to become America’s number one vacuum cleaner brand. Feldmann, who paid $400,000 in cash for the company, merged the two. When the Henney limousine coach-building business fell victim to cheaper rivals and an attempt to create a truck came to nothing, Feldmann brought the two companies under the umbrella of his National Union Electric Company, a manufacturer of heating and air-conditioning equipment.

During one of Feldmann’s acquisitive phases, Henney had inherited a factory that once manufactured school buses in Canastota and, in 1959, this would become the production facility for the Kilowatt.

Although Feldmann was rich he couldn’t fund the development of a new kind of car entirely on his own, so he set about lining up some powerful partners. Union Electric was a major manufacturer of batteries for Exide and Feldmann convinced its chief executive, Morrison McMullan Junior, that a new electric car would be just the thing to drive sales. McMullan Jnr came on board as a developer. Eureka Williams would build the propulsion system and another company, Curtis Instruments, provided the speed controller to a design laid down by scientist Victor Wouk.

Feldmann approached Wouk, who would go on to play a leading role in the development of electric cars and hybrids during the sixties and seventies, for help in developing the drivetrain. He sold Wouk on the idea by telling him that the electric car would be a project for the good of mankind, and invited the scientist to his estate in Stamford, Connecticut, to let him try a couple of prototypes.

Getting Wouk on board was a major coup. After receiving his doctorate in electric engineering from the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), Wouk had developed an ionic centrifuge that was used to purify uranium used by the Manhattan Project during the Second World War. After the war, he set up a company to manufacture AC/DC convertors. By the time he received a call from Russell Feldmann, Wouk was an acknowledged world leader in his field.

The visit to Feldmann’s Stamford estate couldn’t have gone better. Indeed, the cars were so easy to drive that even Wouk’s son, who was 12, could master the controls, but it was obvious that the propulsion system wasn’t ready for the market. According to Wouk, Feldmann had chosen the Dauphine to be the donor car because it was considerably smaller and lighter than American cars of the time. Intrigued by the possibilities, Wouk, who was the brother of writer Herman Wouk (The Caine Mutiny, Winds of War), agreed to bring his expertise to the project.

Jubilation at Wouk’s involvement was short-lived, however, and his conclusions would come as a major blow to the Kilowatt project. After driving the car, measuring the performance and consulting with colleagues at Caltech, he concluded that the lead-acid batteries the Kilowatt was using simply weren’t up to the job. Wouk believed the problem could be solved but the development cost was too much for even Feldmann’s deep pockets, so the millionaire ignored his advice and pressed on regardless.

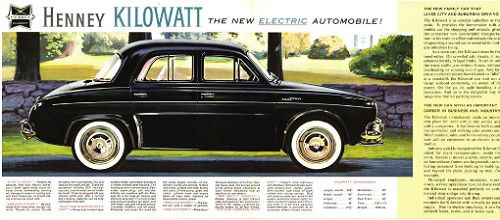

In 1959, the Henney Kilowatt was launched. A proper four-door saloon with room inside for the driver and three passengers, it was advertised as the ‘silent, dependable, simple, versatile, uncomplicated and undemanding’ electric car of the future.

Available initially to electric utility companies, the first ‘customer’ was, somewhat unsurprisingly, Feldmann’s own National Union Electric, which took delivery of twenty-four Kilowatts in 1959 and a further eight the following year. The first models ran on a 36V system of eighteen sequential 2V batteries and had a modest top speed of approximately 30–35 mph (50–56 km/h).

For the 1960 model year, engineers at Eureka Williams replaced the 36V system with a more powerful 72V drivetrain, which boosted the top speed to nearly 60 mph (90 km/h) and increased the range to 60 miles (90 km).

Due to the weight of the batteries, the Kilowatt had a torsional stabilizer at the front, heavy duty coil springs and an ‘air stabilizer’ on the rear.

This second-generation Kilowatt was made available to the general public. Henney’s advertising literature described its operation as ‘light switch simple’. The six-step control was operated via a conventional accelerator pedal. Changing direction from forward to reverse was a simple matter of moving a switch on the dashboard from the forward position to the reverse position. With no gears to worry about, driving the Kilowatt was rather like driving a fairground dodgem car.

The Kilowatt used the standard Dauphine backlit speedometer, which still had gas and temperature scripts on the instrument faces, although the ‘petrol gauge’ was actually a charge indicator. A voltmeter and an ammeter were fitted to the dashboard to show the amount of power being consumed. The windscreen wipers, indicators and horn were all within fingertip reach from the steering wheel.

The company’s advertising emphasized the reliability and smooth running offered by an electric vehicle. The Kilowatt, it said, ‘draws dependability from failure-free electricity. The uncomplicated electric motor is inexhaustible; owners compute cost of its operation and upkeep in pennies. This is the car that redefines “new”.’ The reference to an ‘inexhaustible’ electric motor was somewhat disingenuous when the batteries had such a limited range. After a normal day’s driving the battery could be recharged overnight with the 25 ft (7.5 m) electric cord that was found beneath the bonnet.

According to the sales literature, two models were available. Model A, for urban use, ran on the 72V system, which used twelve 6V batteries. It could be recharged in 8–10 hours and had a range of 40 miles (60km) of constant running or 50–60 miles (80–90 km) if operated in short bursts with stops of 15 minutes or longer to allow the batteries to recover.

The asking price was $3,995. The Model B used an even more powerful 84V set-up consisting of fourteen 6V batteries, which could be recharged in as little as 4 hours using a 220V supply. Set against this extra performance and practicality was the eye-watering asking price of $5,995. Both models featured hydraulic drum brakes, a separate 12V battery for the lights, turn signals and windscreen wipers, a washable interior, a door-operated interior light and locking front doors. The heater was, however, a $400 optional extra and air-conditioning was not available at any price. They were covered by a 6-month warranty.

| Years of manufacture: | 1959–60 |

| Body style: | four-door saloon |

| Motor: | Large frame-size traction electric motor with six-step control |

| Batteries: | 12 x 6V heavy-duty batteries in two banks |

| Recharging time: | approx. 8–10h from AC 110V outlet |

| Range: | 40 miles (64 km) on a constant run or 50–60 miles (80–96 km) if operated with stops of 15min |

| Claimed power: | 7.5 bhp |

| Maximum speed: | 30 mph (40 mph in short bursts) (48–64 km/h) |

| Final drive: | direct from motor to reduction gears and rear axle |

| Suspension (F/R): | Coil springs and shock absorber/coil spring with air suspension units mounted between swing axles and frame |

| Steering: | rack and pinion (24:1 ratio) |

| Brakes (F/R): | Lockheed hydraulic 9 in (22 cm) drums; mechanical parking brake |

| Length: | 155 in (3,937 mm) |

| Wheelbase: | 89 in (2,260 mm) |

| Width: | 60 in (1,524 mm) |

| Height: | 57 in (1,447.8 mm) |

Feldmann hoped that the Kilowatt would prove attractive to bored housewives who would appreciate its ease-of-use, but he was wrong. The car was a massive flop. Approximately 100 Kilowatts were manufactured during the 2-year production run but only a mere forty-seven were actually sold and most of them went to National Union Electric.

Having already taken delivery of the Dauphine bodies from Renault, Henney soldiered on into 1961 using whatever components were available to fulfil orders, but the public remained indifferent.

Feldmann was years ahead of his time. His dogged determination to build an electric car was partly a result of his fear that pollution, caused by the internal combustion engine, was becoming a major problem. But that view wasn’t commonly held at the time. To the ordinary American, petrol was simply a cheap, plentiful source of fuel for cars. Once again, an electric car had failed to find favour with a largely disinterested public.

In 1968, the Mars II appeared. It used a Renault 10 body and ran on four 30V lead-cobalt batteries packed beneath the bonnet and in the boot. Its manufacturer, Electric Fuel Propulsion, claimed the batteries could attain an 80 per cent charge in just 46 minutes. The top speed was 60 mph (100 km/h) and the maximum range 120 miles (200 km). The Mars fared no better than the Henney. Fewer than fifty were made – but not before it became the first electric car to drive on the famous Indianapolis race track.