In 1967, the Governor of California, former actor turned politician Ronald Reagan, signed an act that established the California Air Resources Board, or CARB. The board’s job was to improve the state’s air quality by protecting the public from airborne contaminants. The automobile was directly in its sights.

CARB’s other mandate was to examine and encourage innovative ways manufacturers could comply with impending clean air regulations. Ultimately, this would lead to the zero-emissions vehicle programme, which was responsible for the creation of the pioneering General Motors EV-1 in the nineties.

Back in the sixties, however, growing fears over air pollution and congestion prompted a flurry of interest in electric vehicle technology, led by GM, which initiated a $15m programme that resulted in a couple of interesting prototypes but little else.

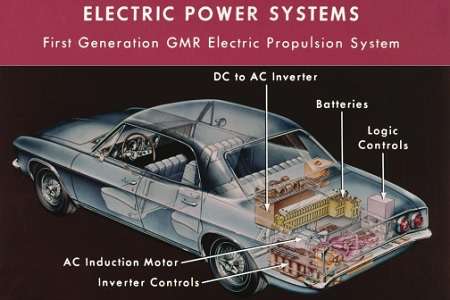

The first GM electric car was based on the Corvair, selected because it was the lightest GM production car available at the time and its rear drive layout made it the ideal donor vehicle for an electric motor installation. The General’s marketing men dubbed it the Electrovair.

The Mark 1 concept used an early model 1964 Monza sedan with the engine and guts ripped out and replaced by a high-speed three-phase induction motor. The rear doors were welded closed in a rather crude bid to stiffen the body sufficiently so it could deal with the considerable weight of batteries slung beneath the bonnet and boot.

The Electrovair II, unveiled in 1966, used the new fourdoor Corvair saloon body. Painted metallic blue, because it was the favourite colour of GM’s Vice President of styling Bill Mitchell, the Electrovair II weighed 800lb (362kg) more than a regular Corvair, thanks to the huge battery packs in the front and back. GM chose silver-zinc batteries because they were able to develop high power.

Indeed, the Electrovair was the most powerful electric car produced by a major manufacturer up to that time thanks to a 115bhp AC-induction motor and a solid-state controller, which gave it comparable performance to a gasoline-powered Corvair.

However, the car’s range was a maximum of 80 miles (128km) under ideal conditions. Its top speed was 80mph (128km/h) and it could do 0–60mph in 16sec. Once again, however, the batteries were the problem. Although the silver-zinc cells gave good power, they didn’t respond well to recharging. Horrified GM engineers found they had to be replaced every 100 charges, making the Electrovair and the Electrovair II non-starters for production purposes.

GM also used the Electrovair II’s innards for a van (the cunningly named Electrovan) but swapped out the silver-zinc batteries for a (even more expensive) cryogenic fuel cell.

The van was enormous – in part thanks to the need to carry liquid-cooled tanks of hydrogen and oxygen in the back – but could cover 120 miles (193km) before the fuel supply was exhausted. The design was a safety nightmare, and during testing several accidents occurred, including a serious explosion that scattered pieces of the Electrovan for a quarter of a mile. Not surprisingly, the dangers of driving a van with tanks of volatile gas in the boot meant the Electrovan was a non-starter for serious production but, as a technical demonstration of what was possible, GM’s fuel cell van was important.

Bizarrely, however, when GM donated the van to the Smithsonian Institute, the world’s largest museum politely declined the offer. The unwanted Electrovan sat gathering dust in a Pontiac warehouse for decades, forgotten about and unloved. The fact hardly anyone knew it was there probably saved it from the corporate crusher. It is now fully restored and on display at the GM Heritage Centre, in Sterling Heights, Detroit.

Having proved to its satisfaction that a large electric car (or van) was not commercially viable, GM changed tack and re-examined the microcar concept. The GM XP512E urban car was shown off in 1969 (alongside a hybrid, the XP512H, and a 300cc petrol-engined version) at the somewhat ironically named ‘Parade of Power’ event.

At least GM’s accompanying press release was brutally realistic: ‘The three cars, with their 30 to 40mph top speed and limited acceleration, would operate either on a paved road system of their own or in reserved lanes of existing roads,’ its said, ‘because they could not mix safely with today’s freeway of boulevard traffic’.

When Mechanix Illustrated tested all three versions, plus the earlier XP511, in October 1969, it wrote:

The all-electric (XP512E) has an 84V power battery plus a 12V unit for taking care of such things as the horn, windshield wipers and turn signals. As we had all [the] cars on the small handling course at the GM Technical Centre, before you could count to 16 in Chinese, Brooks Brender, editor Bob Beason and your… correspondent were racing. There was little difference in top speed and with the cars’ roller-skate type wheels we had a ball.

However, the magazine cautioned:

Whether you will ever get the chance to buy one of these four cars for your Aunt Harriet’s botanical tours is questionable. They were fun to play with and ran very well, but I wouldn’t advise holding your breath waiting for one to turn up at your neighbourhood Caddy dealer.26

The year before GM’s city cars appeared, General Electric demonstrated an experimental electric car called the Delta. A candidate for the ugliest car ever built, the Delta appeared to have been designed by an origami fanatic. The awkward body shape was fashioned almost entirely from flat panels and was so monumentally awful, even Noddy wouldn’t have been seen dead driving around Toy Town in one. GE claimed the Delta had a top speed of 55mph (88.5km/h) and a range of 40 miles (64km) from its nickel-iron batteries. It could carry two adults and a couple of children. After this unprepossessing start, GE wisely gave up on cars and used the Delta’s technology for an electric garden tractor instead.