BORN IN PARIS in 1878, André Citroën’s interest in engineering was sparked by a visit in 1901 to an uncle in Poland, who had patented a gear mechanism with double-helical teeth-the same shape that would later lend itself to Citroën’s famous logo.

On his return, Citroën set up a small factory in the French capital from which to manufacture the gears, while also allowing other companies, including Skoda, to produce them under license. After the outbreak of World War I in 1914, the astute Citroën managed to raise the financing to become a munitions producer. When the war ended in 1918, his business had supplied over 23 million shells to the French army.

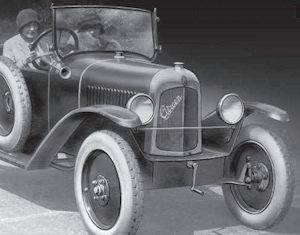

By now a wealthy man, Citroën began making cars a year later. When his Type A 10CV prototype emerged in May 1919, it caused a furore because it significantly undercut established rivals on price.

At the time it was commonplace to order just the chassis from a manufacturer and then have the car’s body made by a coachbuilder; yet here was a complete car fitted out with many items found only on more expensive machines. Citroën received 16,000 orders in just two weeks. Spurred on by this success, André

Citroën then set about developing an entire model range. He was quick to recognize the value of marketing, conceiving new and inventive ways of persuading the public to buy his products.

Launched in 1922, the tiny 5CV three-seater, with its 856 cc engine, was clearly an entry-level car. Citroën’s masterstroke was to target the car at women. It came with an electric starter motor, and the advertising claimed that it was an ideal car for female drivers because there was no need to crank a handle to get it going. Women flocked to buy this accomplished little car. André Citroën could never rein in his spending as he searched for the next “big thing” in motoring.

By early 1934 his range consisted of 76 models, with endless permutations of chassis and bodies. Furthermore, few parts were interchangeable between the different models, and the expense of re-tooling the factory to manufacture each new model ate away at the company finances. Nevertheless, André Citroën continued to push the boundaries.

The innovative 7CV, which made its debut in April 1934, had front-wheel drive and an integrated chassis and body. Even Citroën’s choice of stylist for the 7CV was inspired: He could have had his pick of the best contemporary coachbuilders, but instead he chose the Italian sculptor Flaminio Bertoni, despite Bertoni’s lack of prior automobile experience.

The 7CV was the first of a new family of front-wheel-drive cars that would be united under the “Traction Avant” banner. While these models would be rightly acknowledged as automotive classics in generations to come, customers were initially poorly served, with gearboxes often breaking and cracks appearing in bodyshells.

Most of these issues were quickly rectified, but the firm’s reputation was tarnished. André Citroën’s obsession with spending whatever it took to outshine the rival Renault marque-allied with the dizzying rate at which he launched new models-reached a head in December 1934, when creditors forced the company into bankruptcy.

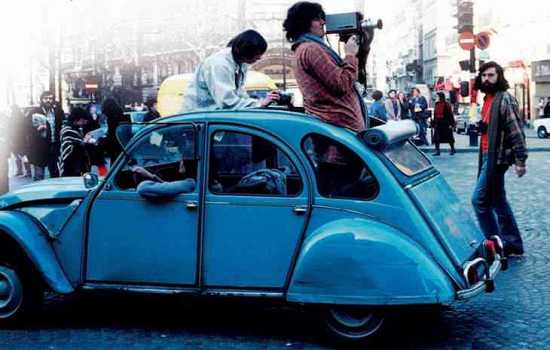

The tire maker Michelin, the largest creditor, assumed control. André Citroën died just six months later, but the firm continued to evoke his pioneering spirit, in particular with the 2CV. Introduced in 1948, this twin-cylinder, four-door car was initially met with derision, but it was cheap and rugged, and remained in production for a staggering 42 years.

By contrast, the DS19 was as daring as the 2CV was simplistic. Launched in 1955, it featured self-leveling suspension and a streamlined body that was styled, once more, by Bertoni. In 1963 Citroën acquired the ailing Panhard marque while also working closely with Fiat on joint projects. However, in 1968 Citroën had to be bailed out by the French government after buying the Italian sports-car maker Maserati. The purchase was a costly error, and in terms of new models it produced little more than the much-admired but unprofitable Maserati-powered SM supercar.

Citroën continued to lose money. New models such as the small GS sedan-voted European Car of the Year in 1971-temporarily helped to boost Citroën’s finances, but this idiosyncratic marque finally lost its independence in 1974, when archrival Peugeot bought a 38.2 percent stake. Two years later Peugot completed its takeover, raising its stake to 90 percent.

Universal appeal Simple and almost rustic in looks, the 2CV was designed to handle uneven rural roads with little maintenance. Yet its small size and economic running made it equally well suited to urban driving, as seen here in Paris.

Some consider the CX, which emulated the GS by being voted European Car of the Year in 1975, to be the last “true” Citroën, since there was a gradual change of ethos under Peugot. In an attempt to appeal to a wider market, 1980s Citroën products, such as the 1986 AX supermini hatchback, became more conventional.

This trend continued in the 1990s, with Citroën models-including the strong-selling Saxo of 1995 and Xsara of 1997-increasingly resembling their Peugeot counterparts. The Citroën marque suffered an image problem as a result, yet it still managed sales of nearly 1.4 million cars in 2003. In recent years Citroën has gained a formidable reputation in rallying, founded on its commitment to showcasing new technology in its competition cars.

In 2004 the French star Sébastien Loeb won the first of six consecutive World Rally Championships with Citroën. As well as being technologically innovative, Citroën has also undergone a design renaissance. The attractively styled DS3, launched in 2009, was the first in a new range of premium cars under the DS banner.