Several manufacturers followed Lohner’s lead by developing their own hybrid drive systems. The Krieger Hybrid, made by the Paris Electric Car Company in 1903, was almost identical to Porsche’s car.

More interesting was the Auto-Mixte, which was made in Belgium from 1906 and used a 24bhp combustion engine, which drove a dynamo via a magnetic disc clutch that was connected to a transmission, which drove the rear wheels via a chain. Regenerative braking helped charge twenty-eight batteries in series, which, under heavy load, could be switched to assist the engine. The car could operate on electric power alone – a mode selected via a hand controller that operated a series of mechanical switches and relays. The dynamo could also be spun backward, acting as a crude electric reverse gear.

This innovative system was licensed from inventor and gunmaker Henri Pieper who had taken the hybrid concept to a new level.

Pieper’s patent application, submitted on 23 November 1905 and granted on 2 March 1909, reveals advanced thinking on parallel-hybrid design that would be dusted down and used in cars like the Toyota Prius a century later. In particular, Pieper realized it was possible to use both electric and combustion power at the same time, as a means of increasing performance.

The patent says:

The invention comprises an internal combustion or similar engine, a dynamo motor direct connected… and a storage battery in circuit with the dynamo, these elements being cooperatively related so that the dynamo motor may be run as a motor by the electrical energy stored in the [battery] to start the engine or to furnish a portion of the power delivered by the set. [It] may be run as a generator by the engine, when the power of the latter is in excess of that demanded, and caused to store energy in the [battery]. As long as the amount of power required falls short of that developed by the engine, the excess is utilized in charging the secondary battery. As soon, however, as an increase in propulsion power is required, as will happen, for example, whenever the car encounters an up-grade, the slackening of the speed causes the dynamo to work as a motor, thus supplying the engine with the additional power which it requires to keep an approximately uniform speed.

Pieper’s drivetrain was very sophisticated for the time. The driver selected various engine modes via a hand-lever. The first used the dynamo to start the engine, another used the battery to supplement the engine and a third charged the battery. In each case the spark timing and fuel/air mixture were adjusted according to the mode – Pieper had created the world’s first engine-management system.

Sadly for Pieper, his brilliant invention was largely ignored by car manufacturers of the day. If his design had been taken up by a major manufacturer, the parallel-hybrid could easily have become the de facto worldwide automobile standard.

Pieper may have been a genius but the only luck he had was bad luck. By the time the patent was granted, the first Model T Ford had already delivered a decisive blow in the battle for market supremacy between electric and internal combustion engines. Only a handful of Auto-Mixte vehicles were built in Liege between 1906 and 1913. The Peiper factory was taken over by another Belgian vehicle manufacturer, Imperia, in 1907 and used for the production of gasoline-powered cars. In a strange case of history coming full circle, in 2009 the Imperia name was revived for a new roadster – to be powered by a parallel-hybrid.

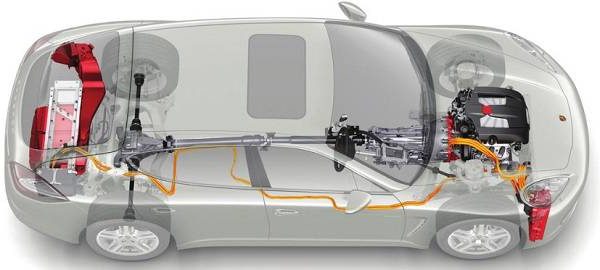

At the same time as Pieper was trying to get his ideas off the ground, Daimler–Benz – anxious to capitalize on the ideas of its new chief engineer Ferdinand Porsche – was preparing a hybrid of its own. The Mercedes Mixte, which was built by the group’s Austrian affiliate, used various gasoline engines, which were permanently coupled to a six-pole dynamo by means of a drive shaft.

The dynamo’s electricity was transmitted to a pair of Porsche wheel hub motors. The Mercedes vehicle used rear-wheel drive (although a few fire engines were apparently built using front-mounted motors similar to the original Lohner–Porsche design) and, although Porsche had refined the concept to make them slimmer, several reporters at the Vienna motor show in 1907 were less than impressed. One wag dubbed them ‘dumplings’ and wrote that they spoiled the aesthetic beauty of the car.

Possibly stung by this criticism, Porsche soon had a Mixte race car up and running. The generator was powered by a 55bhp combustion engine and uprated wheel hub motors transmitted the power to the track. Sadly, the Mixte racer skidded off the track during tests and was badly damaged. Porsche quit Austro-Daimler in 1923 after a bitter row over the company’s future direction.

Beyond Europe, other manufacturers were exploring the benefits of hybrid power. In Canada, the Galt Motor Company of Ontario, used a simple two-stroke engine to drive a 90A Westinghouse generator. Chicago-based Woods – the company formed by MIT grad Clinton Edgar Woods – introduced a ‘dual power’ car in 1916. This used a 4-cylinder Continental engine coupled to an electric motor and cost $2,700. The top speed was 35mph (56km/h).

Even as late as 1921, Owen Magnetic’s Model 60 Touring was still banging the drum for petro-electric drive, with its innovative electromagnetic transmission (the work of George Westinghouse). The Model 60 was powered by an in-line 6-cylinder gasoline engine, which drove a flywheel that had six coils spinning inside an iron housing connected to the driveshaft. Amazingly, there was no direct connection between the engine and the wheels. Instead, the coils created a magnetic field that turned a generator. By all accounts, the transmission seems to have been rather like the Chevrolet Volt when in petrol assist mode – the engine note would stay the same as the speed rose.

The lack of a mechanical connection gave a smoother drive, too. It may sound simple but, with so many fragile parts that could go wrong, the electro-magnetic transmission was hugely expensive to manufacture. Its fiendish complexity and high price meant only the very wealthy could afford the benefits of an Owen Magnetic hybrid driveline. Such knowledge was scant consolation in the event of a magnetic drivetrain breakdown.