In the United Kingdom, electric vehicles were making headlines but, sadly, for all the wrong reasons. Although the much maligned Sinclair C5 is viewed as an object of derision in its home country, it was, until recently, one of the best-selling electric vehicles of all time. What is less well-known is that the C5 was only the start. Had the project gone well, the little plastic-bodied single-seater would have spawned a whole family of far-reaching electric cars. Sadly, plans for a new electric car dynasty were dashed by a combination of bad planning, mischief-making and public antipathy. The C5 was also the undoing of inventor Sir Clive Sinclair.

Although he made a fortune designing and selling gadgets such as the first electronic calculator slim enough to fit in a jacket pocket, the first affordable digital watch and the ZX81/Spectrum home computers that carried his name, Sinclair’s real passion was electric vehicles.

He first aired his ideas while working for the Solartron Electronic Group as a teenager in the sixties. Sinclair espoused the usual reasons for using electricity: clean power, silent running and no pollution. But his employer did not share the same enthusiasm, citing the limited range of a battery-powered motor as a reason for not going ahead. It probably didn’t help that the British motor industry – which was still a force to be reckoned with on the world stage – had just unveiled its own revolutionary response to fears of oil shortages called the Mini.

But Sinclair didn’t give up easily. By the early seventies he was doing rather nicely, selling small transistor radios through his company Sinclair Radionics (an amalgamation of Sinclair Electronics, his original choice of name but one that had already been registered, and Sinclair Radio, which sounded too old-fashioned). Sinclair selected one of his brightest designers, Chris Curry, and asked him to look again at finding a solution to the electric vehicle’s problems.

Sinclair reasoned that an electric car would only be effective if it were a clean-sheet design and not an existing car with batteries in the boot and an electric motor in the engine bay. He was convinced the solution lay in designing a new kind of motor that was more efficient than anything that had gone before.

Curry soon had a prototype engine up and running at St Ives Mill, the old steam flour-mill that was company’s headquarters. It was mounted to a child’s scooter and, provided the ‘driver’ gave it a good shove off with their foot, could power the two-wheeler quite successfully. Sinclair was excited but the unexpected success of his pocket calculator and problems with a digital wrist watch meant he had to put his pet project on ice.

By 1979, however, Sinclair’s thoughts once again turned to the possibilities of an electric car. He approached designer Tony Wood Rogers, who had been the production director at Sinclair Radionics between 1972 and 1978, and asked if he would work on an electric car concept.

Wood Rogers remembers: ‘I reluctantly agreed to do the job on a consultancy basis. I’d worked for Clive before and thought I’d moved on but the idea of an electric vehicle intrigued me.’ The brief was for a lightweight vehicle designed to carry one person, or two at a squeeze, that would be a viable alternative to a moped. As it was to be primarily an urban runabout, the vehicle would have a maximum speed of 30 mph (50 km/h). However, it would be cleaner, more comfortable and, crucially, a lot safer than a moped.

Typical customers would be a housewife who hadn’t passed her driving test and didn’t fancy a moped, a teenager who could not afford a car and households looking for a cheap alternative to a second car. It would need a modest boot, a range of 30 miles (48.2 km) on a fully charged battery, plus the option of an increased range with a second battery (more than enough given that the average moped trip back in 1980 was a mere 6 miles). Above all, it would have to be virtually maintenance-free – something of a novelty for hard-pressed drivers used to the vagaries of British Leyland’s badly built domestic cars.

Sinclair’s plan was to be no mere flight of fancy, however. There were signs that the British Government was now receptive to the idea of an electric vehicle. The Electricity Council, a UK quango, had already spent more than £5m funding research, including £2.3m to Lucas for the Lucas/GM delivery van, and a parliamentary working party had been set up to look at alternatives to petrol. On 26 March 1980, the government abolished motor tax on electric vehicles.

According to Department of Transport figures, in 1978 there were 175,000 electric vehicles in Britain – a tiny percentage of the overall total of 17.6 m registered vehicles. And of those 175,000, only 45,000 were actually in day-to-day use and 90 per cent were milk floats. Sinclair saw an opportunity and, just as he had with the calculator and was about to do again with the home computer, grabbed it with both hands. This was to be the moment he realized his dream.

The plan was for a launch in 1984. So convinced was Sinclair that the public would embrace his concept that he proposed annual production of 100,000 vehicles – an unprecedented figure for an electric car. Sinclair christened this car the C1 (the ‘C’ standing for Clive) and Wood Rogers built and tested several prototypes in a wind tunnel at Exeter University.

For someone with a dream about revolutionizing transport, Clive Sinclair took a very pragmatic view of the batteries that would power his forthcoming car. Although he had raised a considerable sum of money (believed to be around £12m) by selling some of his shares in Sinclair Research, the cost of designing and developing a totally new vehicle was still huge and Sinclair had to make every penny count. Spending millions chasing new battery technology would be a waste of money, he reasoned. Therefore, it would be a better idea to use existing batteries for the new car and, if it was a success, the battery industry would feel compelled to come up with something better.

However, the C1 would need a robust battery capable of at least 300 charge–discharge cycles. Wood Roger says: ‘We were stuck with the standard technology of the time. A car battery was out of the question because it couldn’t stand constant charge/discharge cycles, a traction battery, similar to the kind used in milk floats, could be recharged from flat and a semi-traction battery, often used by caravanners, offered a good compromise. Sadly, though, we had very little freedom of choice.’ The search was ongoing when Wood Rogers received a letter from Joe Caine, a veteran of the Chloride battery company, asking to join the project. No doubt to his considerable surprise, Caine soon found himself established in a research lab in Bolton with thousands of pounds worth of testing equipment.

The C1 project was handed over to Ogle Design, the consultancy responsible for, among others, the Reliant Scimitar GTE, the Reliant Robin, the Bond Bug, the BSA Rocket 3 motorcycle and even Luke Skywalker’s land-speeder in Star Wars.

Wood Rogers says Ogle Design were convinced the C1 would be a flop:

For 12 months all they did was come up with reasons why it wouldn’t work. They said it wasn’t fast enough, that people would get wet when it rained, that the battery wasn’t good enough. They seemed to spend time proving it wouldn’t work. Eventually, they killed it.

However, things changed dramatically in 1983 when a new set of regulations became law, prompting a review of the Sinclair EV project that would have far-reaching implications. The Electrically Assisted Pedal Cycle Regulations introduced a new class of vehicle on Britain’s roads. Although none existed at the time, the government laid down some basic guidelines for electrically assisted cycles. They could have two or three wheels, must weigh less than 132 lb (60 kg) including a battery, contain an electric motor rated at no more than 250 W, be controlled via an on/off switch biased towards the off setting and meet the British standard pedal-cycle braking specifications.

As with the moped laws, the electrically assisted part of the description meant they must also be fitted with pedals. If the Sinclair could meet these specifications, the car would be available to anyone over 14 years, who could drive one without the need of tiresome red tape like insurance, road tax, a crash helmet or even a driving license.

Sinclair and Wood Rogers decided to put the C1 on ice in favour of a much simpler electrically assisted bicycle, which would utilize a two-wheels-at-the-rear-one-at-the-front layout similar to the much-loved Bond Bug mini car. Sinclair still believed he could create a family of EVs and hoped the C5 (as it was now called) would presage more ambitious and technologically superior cars.

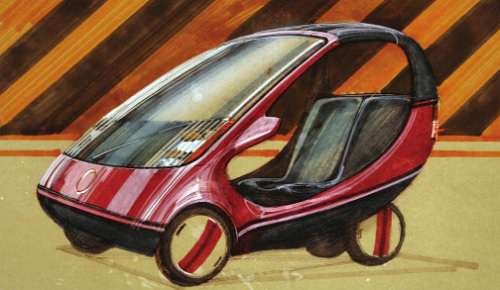

Wood Rogers had been hard at work making this dream a reality. As the C5 took shape, he sketched out a C10 city car and a C15 motorway car:

I’d bought an Isetta bubble car to study and, essentially, the C10 was a more modern interpretation of it. We built a full-scale mock up and it looked great. I specified open sides to keep the cost down and having no doors meant it escaped a lot of regulations, too.

The C10 was capable of carrying two passengers and reaching 40 mph (64.3 km/h). The wide frontal area was carefully shaped in the wind tunnel to keep the rain off – even with open sides. The wide front track meant it was very stable, too. Seen today, the C10 bears an uncanny resemblance to the Renault Twizy, a fact of which Wood Rogers is very proud: ‘It’s nice to know we were so far ahead of the curve. You could put the C10 into production today and it would still look contemporary.’

The larger C15 was an even more ambitious project but Wood Rogers admits it could only have worked if a better battery solution had come along.

For a time we hoped sodium sulphur [batteries] would be the answers. They were supposed to be the holy grail of battery tech but thermal problems meant they never got off the ground. The only way we could have done a motorway car back in 1984 was with that kind of battery.

In the meantime, Sinclair turned to Lotus cars to help him design and engineer the C5 ready for launch. Although he actually considered buying a share of Lotus, Sinclair finally settled on a standard contractual arrangement. Negotiations were helped by Barrie Wills, a motor industry veteran who had joined Sinclair after a spell at the ill-fated DeLorean factory.

Wills had a long-standing relationship with Lotus – it had done much of the design and engineering work on the DeLorean car before it went into production at the Dunmurry factory, south of Belfast, in Northern Ireland – and would become an effective link man between the two companies.

Work on the C5 had begun at Ogle Design. Ogle had also created the Bond Bug, which possibly explains why the C5 bore an uncanny resemblance to that car, but Lotus took the design to the next level, trimming weight and refining the pressed steel chassis.

Over a 19-month period, the C5 was extensively re-engineered by Lotus and tested at the Motor Industry Research Association proving ground, in Leicestershire, under conditions of utmost secrecy. One of the first on-the-road tests was conducted on 29 July 1981. The day had been deliberately chosen because it was the wedding day of Prince Charles to Lady Diana Spencer and millions of people would be indoors glued to their televisions. The C5 was also put through its paces at the Prescott hill climb, where both hill-climbing ability and braking performance were examined. Parts of the track were flooded and bad-weather performance-testing was done in sleet and snow.

Wood Rogers had decided at the outset that the C5 would use a handlebar arrangement to steer the front wheel. ‘A steering wheel would have made it impossible to get in and out easily and that could have been dangerous in a crash,’ he says. ‘Putting the bars at the driver’s sides made it easy to steer and felt very natural.’ Building an adjustable set-up would have added too much cost. The shape of the vehicle was revised by a 23-year-old graduate of the Royal College of Art called Gus Desbarats. Wood Rogers says the C5 design was almost completed when Desbarats arrived and all the key hard points were set in stone.

In an interview with The Times to mark the twentieth anniversary of the C5, Desbarats remembered:

Clive was hoping that the design would need only minor changes but I had to advise him, on day one of my working life, that I thought we should start again. He stared at me, asked me how long I needed. I said four months and he gave me eight weeks.

Desbarats added a small boot and extra cushioning to the seat. The designer didn’t feel comfortable being so close to the ground, so he also added a vertical safety mast – but the shape essentially followed the form of the pressed metal chassis.

Meanwhile, Wood Rogers had found a suitable motor – designed originally to power a truck’s cooling fan and not, as is often said, a washing machine – which delivered the required 250 W output. Joe Caine had developed a suitable battery, which could be 80 per cent charged in 4h at a cost of less than 5 p. It weighed 33 lb (15 kg), which meant a spare could be carried and the C5 would still not exceed the 132 lb (60 kg) maximum stipulated in the new regulations. With two batteries – the so-called touring configuration – the C5 had a range of 40 miles (64 km).

At launch, Sinclair claimed the C5’s body was the largest injection-moulded polypropylene shell in the world. The upper and lower pieces, which were supplied by ICI, were bonded by means of a tape that was heated up via an electric current – effectively fusing the two parts together. The same process had been used to make the front and rear bumper assemblies of the British Leyland Maestro. This simple process took a mere 70sec and was perfect for mass production. Each mould was capable of producing 4000 parts per week.

Sinclair had briefly flirted with the idea of buying the defunct DeLorean plant in North Ireland. The factory, built on the site of a peat bog, would have been ideal for his dream of a family of electric cars (it had a notional capacity of 300,000 cars a year) but negotiations dragged on too long for the administrators of DeLorean’s assets.

However, when word of Sinclair’s ambition reached the Welsh Development Agency it brokered a deal with Hoover, which owned a modern facility in Merthyr Tydfil with space for the C5 production line. In April 1984, a hand-picked team was established to begin assembling pre-production C5s. They operated in conditions of great secrecy in a part of the factory that was sealed off from the rest of the Hoover facility. At the same time, Hoover began work on a much larger production line, capable of meeting Sinclair’s ambitious production figure of 200,000 C5s per year, on the other side of the Cardiff–Merthyr road, which was linked to the existing factory by an underground tunnel. Twin production lines could produce 100 vehicles per hour and, with a shift pattern, the factory was capable of churning out up to 8,000 per week.

The C15 would have been Sinclair’s ‘ultimate’ electric car, capable of travelling at 70 mph (112 km/h) for more than 100 miles (160 km).

Production began on 1 November 1984, as the company began to build up stocks ahead of a launch early the following year. The C5 was assembled on a conventional production line, which finished with a rolling-road test that simulated the weight of a 12-stone (75.6 kg) driver, to check for any vehicle defects prior to despatch. Once the vehicle was given the all-clear, it was packed in a cardboard box that travelled on a conveyor belt to the despatch area, where they were loaded into a lorry and sent on their way to one of the three regional distribution centres in Hayes, Preston and Oxford.

The C5 was launched to an expectant press at Alexandra Palace, in London, on 10 January 1985. Sir Clive announced that the vehicle was the first of what was to be a full range of electric cars. In a masterstroke of understatement, he said:

We are not announcing a conventional car. Sinclair Vehicles Limited is dedicated to the development and production of a full range of electric cars, but today we have an electric vehicle, the first stage on the road to the electric car.

Barrie Wills went further, hailing the C5 as the first in a ‘family of traffic-compatible, quiet, economic and pollution-free vehicles for the end of the nineties’.

Addressing what was to be one of the C5’s biggest problems, Sinclair said:

We’ve gone to great lengths to make the vehicle very visible, both in daylight and at night, and to make it tough. We’re very much of the view that, by encouraging people to be on three wheels rather than two, we will be adding considerably to safety on the road.

The cars made a dramatic entrance – bursting forth from cardboard boxes driven by promotions girls dressed in grey outfits to match the C5’s battleship grey plastic bodywork. The C5 press pack bought into the hyperbole, glossing over the 15 mph (24 km/h) top speed in favour of claims that the vehicle could ‘run at the speed of an Olympic sprinter’.

Sinclair was ahead of the game in other areas, too. At launch, Sinclair showed off an extensive catalogue of customization options and spin-off merchandise, including pullovers, hats, mugs, bags, caps, key rings and even a C5 video game (playable on a Sinclair, naturally). On a more practical note, the all-weather C5 owner couldn’t be without the official clip-on side-panels, which cost £19.95 per pair, and tonneau cover, a snip at a mere £7.95.

A more expensive option, at £34.95, was the Sinclair weather-cheater, a waterproof jacket, which, according to the official catalogue, was a ‘fashionable piece of leisurewear in its own right’. Other extras in included an indicator kit, the high-visibility mast, seat cushions and a booster pad for younger drivers. A ‘free’ accessories catalogue was in the box with every C5 sold.

To launch the C5, Sinclair spent £3m on advertising, including full-page national press ads and a television commercial. The theme was that the C5 represented a ‘new power in personal transport’. The price of this new power? A mere £399, plus a cheeky £29 postage and packing fee, with no need for road tax or driver’s licence. Perhaps mindful of Desbarats’ worries about driving a C5 in traffic, every one also came with a free copy of A Guide to Safer C5 Driving, written by the Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents.

Initially, the vehicle was only available by mail order, while Sinclair tried to thrash out a distribution deal with the regional electricity boards. In the meantime, buyers could place their order at Comet electrical stores and hundreds did so. Export sales were planned to Italy, France, Germany and Holland.

The Mayor of Scarborough was so impressed that he gave up the use of his official Daimler for a C5. Councillor Michael Pitts said if everyone followed his example the North Yorkshire seaside resort’s parking problems would be solved overnight. The first C5 ‘race’ took place in the North-East where the mayors of Darlington and Barnard Castle pedalled a couple of C5s around a track for charity.

But the launch euphoria soon turned sour when concerns over the C5’s safety emerged. Just 24h after the launch, Cleveland County Council called for the vehicle to be banned from public roads. The authority’s highways and transportation committee said it was ‘criminal’ of the UK’s Department of Transport to allow unregulated use of the machine. Committee chairman Paul Harford said: ‘I fear what might happen if someone driving one of these comes upon heavy traffic. It’s so low on the road that they could get choked by the exhaust fumes of a lorry…’.

Despite a glowing endorsement from the Greater London Council, which dubbed it ‘a positive advance in road safety’, anxious parents were horrified at the idea of letting a 14-year-old out on the road in a C5. The poor top-speed meant drivers were forced to the side of the road with cyclists – fine when the road in question was smooth but a big problem in towns where gully grates and assorted debris awaited the unwary.

Questions were asked in Parliament and Transport Minister Lynda Chalker was forced to defend the vehicle, declaring it to be ‘no more dangerous than a pedal cycle’.

The vehicle’s reputation was hardly enhanced when newspapers reported how some drivers had bought C5s to avoid serving drink-driving bans because they required no licence (although, judging by the ridicule C5 owners suffered, a bicycle or a stout pair of walking shoes would probably have been a better choice). Student Nicholas Botting had the dubious distinction of being the first C5 user to be charged with drink-driving after volunteering to drive a girl’s C5 home from a St Valentine’s Day Ball, in London. The case was thrown out when prosecutors were unable to prove the C5 was a car.

Soon Comet was discounting the vehicle – offering to waive the delivery cost, then slashing the asking price – as unsold stocks began to build up at the Hoover factory.

In June, the C5 was slated in a road test by the influential Consumers Association, which concluded it was ‘of limited use and poor value for money’. The report, published in Which? magazine, examined the vehicle’s braking, speed, acceleration, safety, durability and reliability. Testers found it hard to keep up with traffic due to a mere 13 mph (21 km/h) top speed on a fully charged battery. Other disadvantages were no speed control on the motor, the lack of suspension, which meant even shallow bumps were felt with bone-crunching force, the non-adjustable seat and pedals, and the poor boot space.

By the beginning of August the game was up. Hoover, alarmed at growing debts, called a halt to production and put the factory into mothballs. Creditors appointed liquidators after hearing the company was in the red to the tune of £6.4m. At the creditors’ meeting, held in Coventry in November, Sir Clive was named as the biggest creditor being owed £5.9 m. Some 4,800 C5s were unsold out of a production run of approximately 9,000. Overall, Sir Clive himself had lost £8.6m on the venture.

Another problem was the lack of any weather protection. An umbrella was impractical but Sinclair sold its own range of waterproof clothes.

Although the C5 put the electric vehicle concept on the map in the UK, its failure did untold damage to the image of electric cars. Subsequent EVs became the butt of endless C5-related jokes and the stigma of owning and driving an EV in Britain was not overcome until the arrival of the Toyota Prius in the late nineties.

Undaunted by the C5’s demise, Sir Clive carried on his work with electric vehicles, first with the Zike, an electric bicycle, in 1992 and ‘son of C5’ the X-1, an electric bicycle with an egg-shape acrylic bubble body in 2010.